Up Close

Until I determined that my work could only make sense to me right now if it addressed the current state of the environment, I never thought about the Hudson River School painters, and, in fact, other than being amused by Bierstadt’s sensational exaggerations, I agreed with critic Phillip Kennicott when he wrote in the Washington Post that Hudson River painters were “[spinners] of romantic cotton candy.” But as I reflected about what we have been doing to the planet, and specifically to my homeland, which is America, it made sense to look back at the first American landscape painting movement and use that as a vantage point for looking forward to now, nearly 200 years later. Looking through this lens at the America we inhabit now isn’t a conceptual stretch at all. The Hudson River School paintings, especially those by Cole, Church and Bierstadt, were, yes, highly romanticized depictions of idealized pastoral “nature”, but I would argue that their artifice is not much different than our currently curated experiences of nature - from decorative plantings in shopping centers, to fenced walking paths through state parks, to manicured personal and public gardens, to Disneyland. So much of the American landscape has been organized, privatized, commercialized, manicured, and ultimately depleted. We bury our trash in the land, hide decay and pollution behind walls, and fence off anything aberrant - and we ignore the historical violence of colonial genocide that is embedded in the American landscape - isn’t this how we romanticize our contemporary experience of American “nature”?

It felt important to look, directly, at the work of the Hudson River School painters, and also at the first landscapes, in the Hudson River Valley itself, where they hiked and sketched. That’s what I am doing this week.

The ground was still damp as I walked the mile to the West Building of the National Gallery, past the Capitol Building. I arrived at 11:00, walked through the metal detector, my bag was searched, and then I checked my bag, keeping my phone and my notebook, and headed straight for galleries 60, 64, 66, 67 and Lobby C.

The National Gallery has an impressive collection from the Hudson River School - Cole, Church, Bierstadt, Church, Cropsey and Moran - but also Kennsett and the outlier, Heade.

The presence of something is visceral - it involves the whole body, not just the eyes (as in seeing something on the computer screen), and so what always strikes me first is a painting’s scale to my body. A painting is almost always smaller or larger than I expected. It is something that is difficult to share here.

A few paintings in particular really struck me, which I note here in chronological order - it is interesting to see how the approaches change:

Thomas Cole, Sunrise in the Catskills, 1826. Detail below.

Frederick Church, Newport Mountain, Mount Desert, 1851. Detail below.

Albert Bierstadt, Buffalo Trail: The Impending Storm, 1869. Detail below.

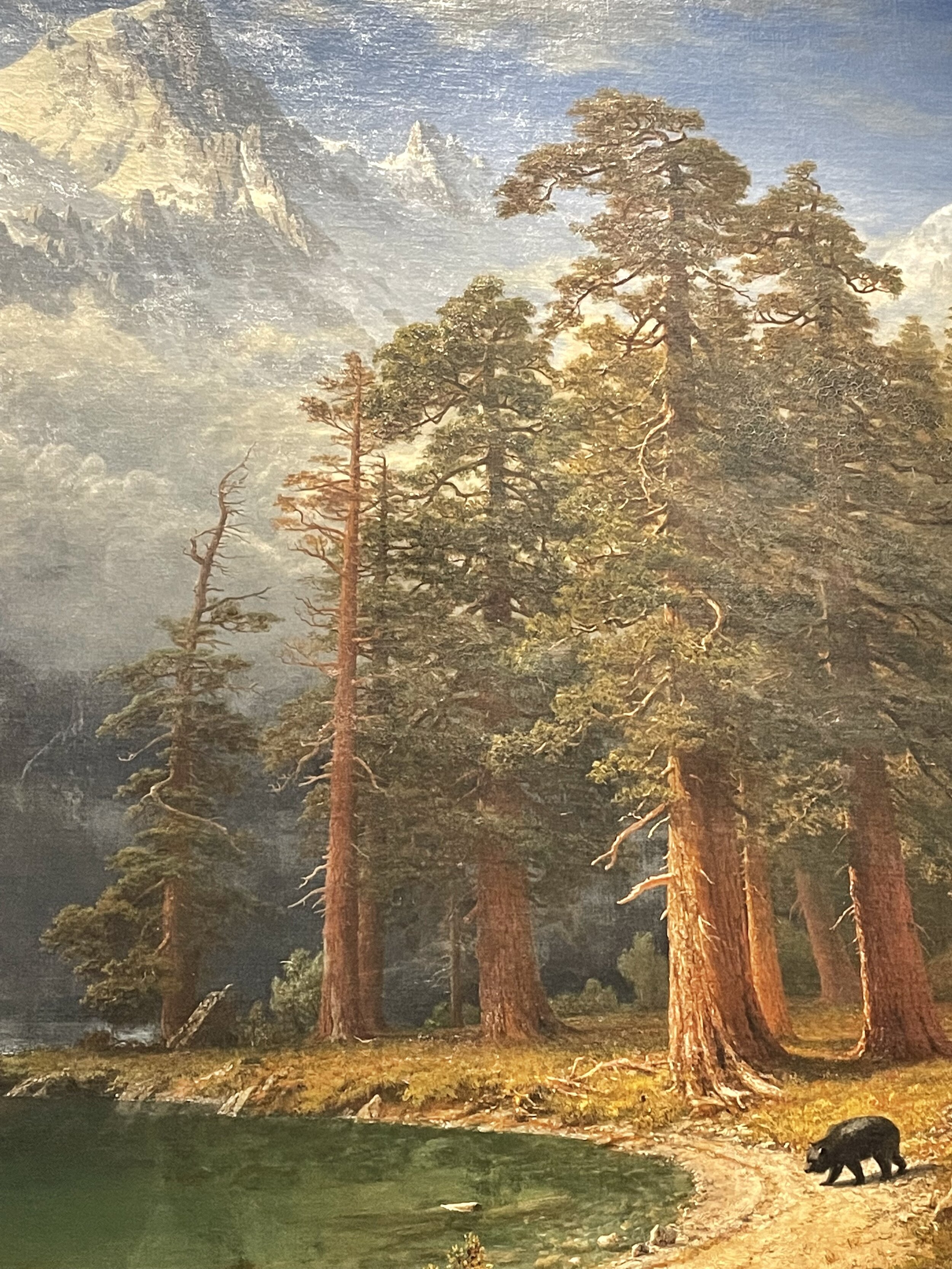

Albert Bierstadt, Mount Corcoran, 1876. Details below.

Frederick Church, El Rio de Luz, 1877. Detail below.

Albert Bierstadt, The Last of the Buffalo, 1888. Details below.

While there is so much to write about (and I will in future posts), there were a few things I noticed immediately - skillful atmospheric perspective, framing trees (repoussoir trees), a path or angled edge that leads into the picture, and dramatic uses of light and dark areas.

At 2:00 I had an appointment to view 15 works on paper that I had requested to see - works that are in storage. I went back to the information desk and asked the attendant to call Curitorial Assistant Caitlyn Brague, who walked me behind closed doors to the drawings and prints study room. I spent two hours in amazement there, especially while examining the stunning watercolors of Thomas Moran, which he created on site. The sketchbook of Bierstadt, which was fragile, was an honor to see - as sketchbooks document thinking and exploration. It is the work before the work that I wanted to see - the figuring out - the thought process - the discovery.