The Land on Which the Cole House Sits

Cedar Grove - Thomas Cole House

Thomas Cole’s yellow house in Catskill, NY is a modest farmhouse with a porch along the width of its front. It is walking distance to the river, and across the river from where his student, Frederick Church, would build his lavish and large home, Olana, on land with vistas Church would design.

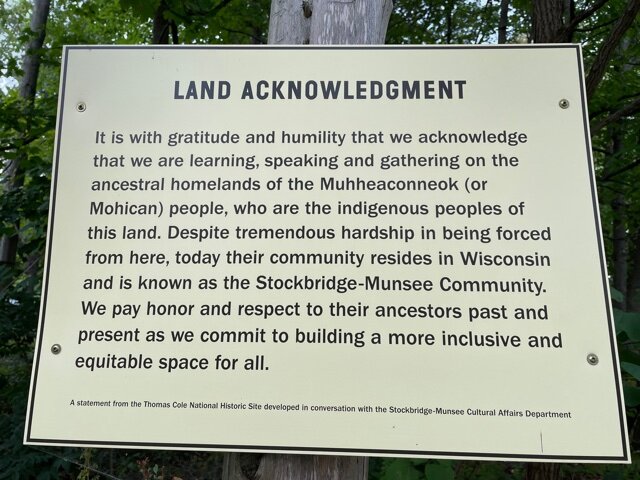

The land on which the Cole house sits is the homeland of the Algonquins or Muhheaconneok (people of the waters that are never still), or who are often referred to as Mohicans. They lived on the land for at least 7,000 years.

According to Sherry White, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer at Stockbridge-Munsee Tribe, “from Manhattan to Vermont, it is pretty hard to put a shovel in the ground without hitting a [native] site of some sort…” This is absolutely true of the Hudson River Valley.

Now, because of genocide and colonialism, the 1,500 Muhheaconneok from what we now call the Hudson River Valley who survive today live in Wisconsin.

The land acknowledgement at the Thomas Cole house.

The Muhheaconneok named the river Mahicannituck.

White men named the river after Henry Hudson, an English explorer who made two unsuccessful sailing voyages in search of an ice-free passage from Europe to Asia. Then, “in 1609, Hudson joined the Dutch East India Company as a commander. He took charge of the Half Moon with the objective of discovering a northern route to Asia by heading north of Russia. Ice put an end to his travels, but this time he did not head for home. Hudson decided to sail west to seek a [western] passage to Asia. According to some historians, he had heard of a way to the Pacific Ocean from North America from English explorer John Smith.” (biography.com)

During this third trip, Hudson explored New York Harbor and sailed up the Muhheaconneok to present day Albany.

Upon his return, the English were angry that he had been exploring for the Dutch and forbid him from working with the Dutch again. Still eager to find the elusive Northwest Passage, Hudson found English investors for what would be his last voyage, on the ship Discovery, and set sail in April 1610. He skirted the southern edge of Greenland and eventually ended up in Canada’s Hudson Bay. Winter descended, food was in short supply, and they were trapped by ice. Food was rationed and crew members became sick with scurvy. Months later when things warmed up, the ambitious (and perhaps narcissistic?) Hudson wanted to keep going, but his crew wanted to go home. They mutinied. The fed-up crew put Hudson, his teenage son, and a few faithful crew members in a small boat and set it adrift. The Discovery returned to England, and Hudson and everyone else in the small boat disappeared. They likely perished in or near Hudson Bay. We don’t know the details of how that story ended, although a stone was found in 1959 engraved with “HH CAPTIVE 1612”…

At any rate, that must have been a one horrible winter for the crew.

Indians Trading with the Half Moon, Henry Schnakenberg, Fort Lee, New Jersey Post Office, https://postalmuseum.si.edu/indiansatthepostoffice/mural13.html

When the Dutch arrived, the people who lived on the land where Thomas Cole’s house sits were agriculturalists. They grew corn, beans and squash and gathered hickory nuts, walnuts, acorns, chestnuts and berries. They hunted bear, elk, deer, rabbits, squirrels, river otters, raccoons, wood chucks, fish and waterfowl. They lived in wigwams and long houses. Women had roles of authority. Ceremony and teaching were important parts of their community life.

When the Dutch arrived the Muhheaconneok were living complex, rich lives.

Europeans brought smallpox, measles, diphtheria and scarlett fever with them, which killed thousands of Algonquins who had no immunity.

Due in large part to Henry Hudson’s exploration of the Mahicannituck (Hudson) River, the Dutch West India Company forged a fur trade alliance with the Mohawks, depleting the animal population, which in turn made the Native population dependent on the Dutch.

In 1647 the Dutch were at war with the English along the Connecticut River. They attempted to build a fort half way up the Mahicannituck (Hudson) River, but the British invaded and took control of New York City and the Mahicannituck (Hudson) River.

Between 1680 and 1708, much of the Munsee land was sold to the British. Native communities stopped living traditional lives as the British sought to “civilize” them. Native children were sent to Indian Residential Schools (mostly Christian missionary schools) to assimilate native youth into Euro-American culture.

The Europeans basically killed the Indigenous people physically, culturally and spiritually so that they could take the land and its resources.

A Dutchman, Gysbert uyt den Bogaert, bought 460 acres of land from the Muhheaconneok in 1684 - the land on which the yellow house sits today. After his last descendant died, the land was divided and sold by speculators.

Dr. Thomas Thompson and his family bought one of the portions of the land and leased neighboring lots until the property grew back to a third of its original size, 155 acres. The Thompson family built the yellow house in 1815 and named the property Cedar Grove.

When Dr. Thompson died, his brother John took over the property and it became a working farm with profitable orchards. Four of his orphaned nieces lived with him.

By the time Thomas Cole visited (and was awed by) the Hudson Valley in the early 1830s, the Muhheconneok and Munsee were gone.

Cole had a studio in New York city, but he rented a cottage on the property from the Thompsons so he could live and paint in the Hudson Valley. In 1836 he married one of the orphaned nieces, Maria, inside the yellow house. His studio at Cedar Grove was a separate barn on the property (see video below), where he painted Lake with Dead Trees and Kaaterskill Falls.

Seven people lived in the yellow house with Cole. Small bedrooms upstairs encircle a landing at the top of the stairs. Thomas and his wife shared one bedroom, the three Cole children shared a second bedroom, and Cole’s wife Maria’s three unmarried sisters shared the third bedroom.

In 1846 Cole built a new studio on the property, which he worked in for only 18 months, until he died of pneumonia.

Frederick Church, who became Cole’s student when he was 18, was a friend of the family. Many artists visited after Cole’s death. But it was economically challenging for Maria, their three children, and Maria’s three unmarried sisters. Church helped. He hired Cole’s son to work on the property he was designing at Olana. Meanwhile the Cedar Grove property was made smaller by the addition of a road and a reservoir, and Maria sold additional parts of the land. The construction of the Rip Van Wrinkle bridge in 1933 threatened to demolish the house, but the Cole decedents fought the effort and the location of the bridge and road were shifted. By the 1930s, the Hudson River School paintings were in disfavor, respected only for their historical significance.

The double dash black lines above show where the road and (over the river to the right) then bridge were built and how it cut into the Cole property. You can see how the plan for the road had to curve up to avoid destroying the house.

The Rip Van Wrinke Bridge, build in 1933, across the Hudson River in Catskill.

It took efforts from artists and conservationists and the Greene County Historical Society to save the house from being privately sold or destroyed again in the 1960s. Cole’s original cottage and second studio were destroyed. In 2016, a replica of the second studio was rebuilt and serves now as a gallery.

A few things struck me deeply during my visit:

The juxtaposition of multiple projectors on the ceiling above original Cole furniture (the chairs which exactly matched those in my own grandmother’s house) highlighted the 150 years between Cole’s time on earth and mine. The Greene County Historical Society created an excellent video and audio introduction for visitors, using the writings of Thomas Cole, spoken by a British actor, with a focus on Cole’s concerns about what industrialization was doing to the land. It is rare to hear the words of an artist unmitigated by a historian or “expert”. He says:

“I have found no natural scenery which has affected me so powerfully as that which I have seen in the wilderness of America. Yet, I can not but express my sorrow that the beauty of such landscapes is quickly passing away. The copper-hearted barbarians are cutting all the trees down in the beautiful valley in which I have looked so often with a loving eye. This throws quite a gloom over me. The ravages of the axe are daily increasing.”

“I will create a series of pictures that illustrate the history of a natural scene affected by man, wherein we see that our nations have risen form the savage state to that of power and glory and then fall again and become extinct.”

He wrote those lines 150 years ago. He could sense what was coming because he was living in the middle of an explosion of colonialism and industrialism.

By the time Cole began painting, the native population had experienced genicide, land had been clear-cut for farming, and the railroad was becoming a major transportation force - all of this changed the landscape in significant ways.

1853, Peanut Line passenger train at Honeoye Falls station, crookedlakereview.com

Beginning around 1830 and continuing over the next 25 years, when Cole was in his 30s and 40s, multiple railroad lines were built from New York through the Hudson River Valley and to points further north and west.

Just five years after Thomas Cole died, in 1853, the New York Central Railroad was formed when 10 smaller rail lines merged.

By 1890, 163,597 miles of railroads stretched across the entire United States, destroying and dividing land, creating habitat loss, species depletion, air, soil and water pollution.

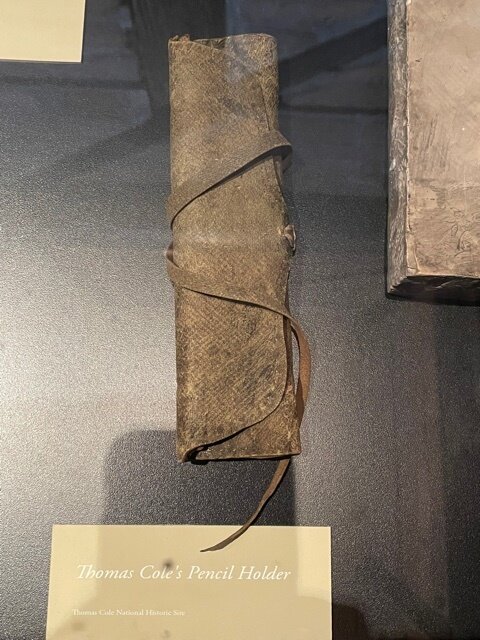

Wandering through the Thomas Cole house without a guide, I spent as long as I liked anywhere on the property. Objects that Cole used every day - his desk, a chair, a pencil case, a paint brush, a paint box - are still there, and I tried to touch into these things - to imagine him there - to make it present tense - imagine conversations - the sounds of shoes on the wood floor.

On view were daughter Emily Cole’s botanical illustrations painted on commercially-produced tea sets. It was not considered proper for women to paint - but I want to investigate this more, as my contemporary self finds it hard to accept that Cole would not have encouraged her.

Cole’s pressings of plants struck me, too - these plants are 150 years old - laid out on the paper with care by Cole, with notes in his handwriting.

Inside the house currently is part of a contemporary exhibition titled “Cross Pollination”, which is on view at the Thomas Cole house and at Olana. Three of the works here were powerful for me:

Pink Forest with Stump, 2016, by Patrick Jacobs - a delicate pink world imbedded in the wall. The delicacy of the landscape is highlighted by the tiny-ness - maybe 6 inches across? - of this little world.

Ornithology L, Ornithology M, and Ornithology J, 2018, by Juan Fontanie, inspired by Martin Johnson Heade, using cut-outs from 18th and 19th century natural history illustrations and powered by Victorian clock motors. Pure joy.

The Eclipse, by Susannah Sayler and Edward Morris is a gorgeous piece. I encourage you to listen to Sayler and Morris talk about the work on this audio file before watching the video.

And most of all, the tree in front of the house, which shows up as its younger self in paintings of Cedar Grove. I thought about how that tree saw all of Cole’s life there, and everything that has happened since - 150 years of time. That tree holds so much change, time and experience in it’s truck.

And the land holds all that came before the tree, including the spirit of a community of people who had deep respect and care for the land we have divided and plundered for more than 200 years.

Much of the history I wrote in this post comes from the work of historian Robert S. Grumet as well as Wikipedia.

The Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican Nation’s website is www.mohican-nsn.gov